Loring, by Wyle (top photo)

One of the biggest problems with so many oversimplifying explanations of how society ‘really’ works is that these theories always seem to leave out one of the most interesting and important parts of any society – its willful and often unstoppable productive eccentrics.

They aren’t toeing the line, following the established schools, rules or patterns. They don’t fit a demographic, and their emergence, effects and repercussions aren’t mathematically predictable, no matter how clever the theory. They are gloriously humane weirdoes – black sheep with generous spirit and often an improbably brilliant perspective – and we are all very much the richer for the way their personal quests and commitments advance our shared culture.

Wyle, by Loring

Florence Wyle (b Nov 24 1881) and Frances Norma Loring (b Oct 14th 1887) both began life in the USA – Wyle in Trenton Illinois, and Loring in Wardner Idaho. A determined intellectual from youth, Wyle’s early aspiration was to become a medical doctor. At the age of 19, she enrolled at the University of Chicago as a pre-med student, and she stayed with the program which back then included drawing in first year and painting in second year. It was third year sculpture which convinced her to transfer over to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1903, which is where she was to meet Loring in 1906.

Loring’s early life proves she had both rare talent and encouraging parents. She was only fourteen when she enrolled to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Geneva – where she remained for two years before moving to Munich to study with sculptor Carl Guttner for a year, and then moving again to study at the Academie Colarossi in Paris.

All of this wide ranging instruction and experience before she arrived at the Art Institute of Chicago and met the woman who would change the course of her entire life. Still, she only stayed a year at the Art Institute (1906) before moving on to study at the Museum of Fine Arts (at Tufts) in Boston and later the Art Student’s League in New York (1910).

In 1909, Loring moved to New York and Wyle followed a few months after. They shared a converted stable in McDougall alley, the heart of the Greenwich village artists community, which is where they first started working on busts of one another. They moved to Toronto in 1913 – settling first on the second floor of a former inn at the corner of Church and Lombard, which had been converted into a busy carpentry shop. This is where many of their famous early commissions and monuments from the first world war period were planned and executed.

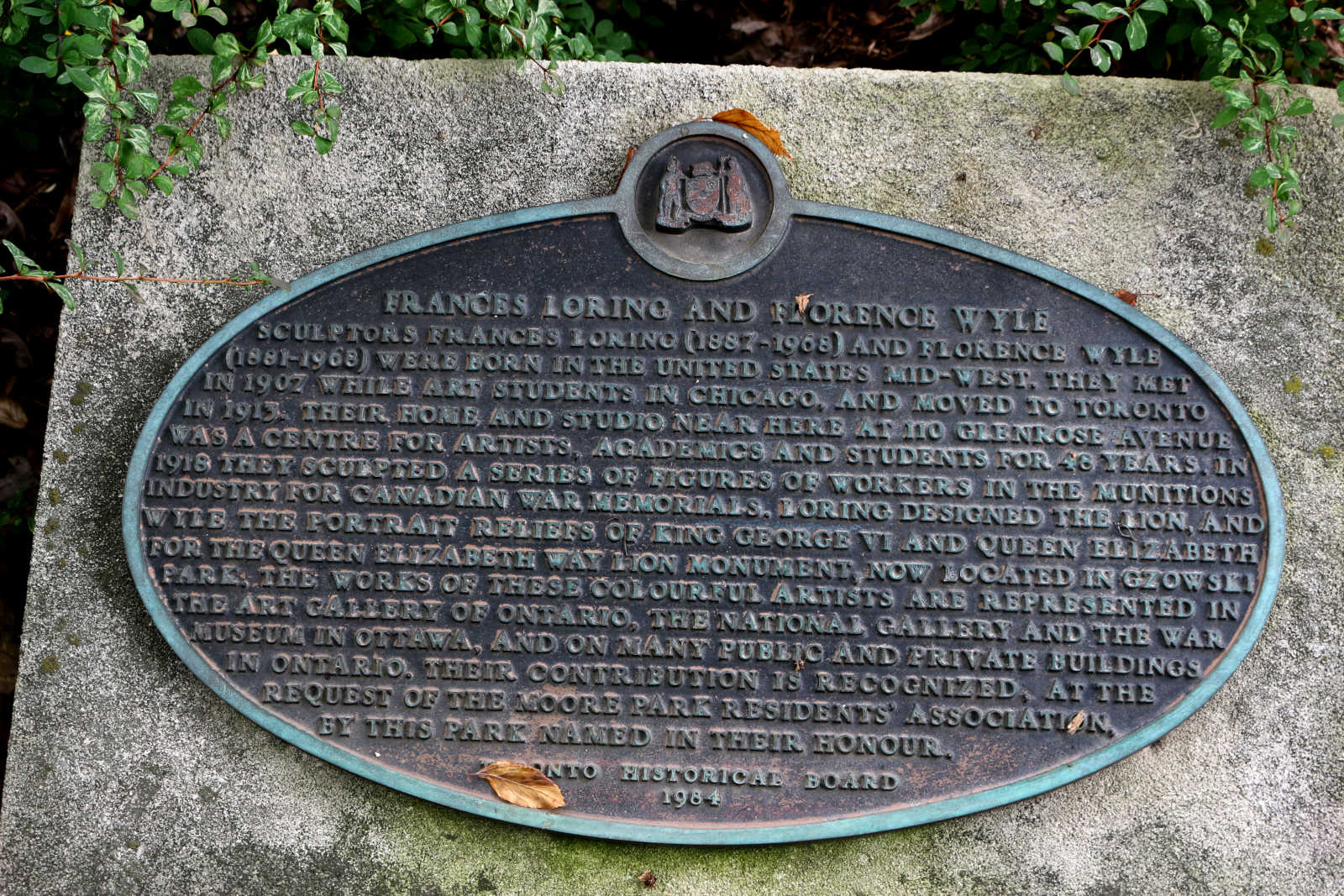

By 1920 they had finally saved up enough money to buy their own place, and settled into an old church schoolhouse on Glenrose avenue just outside the city in Moore park (now in busy midtown, but still quite lovely), where they would live and work together for almost half a century. A small park dedicated to the two of them now sits just next to the site of their beloved ‘Church.’

But already I am mainly describing dates and turnings, which is vastly underselling these two. They weren’t just super productive artists – doing both superb art deco style public memorials and fine modern art – together, they were a serious (and also insightful, witty and hilarious) force for cultural change and art promotion in the city and the nation as a whole.

Right from their arrival in (back then on the swampy edge of) town, they were known as “The Girls” and were soon legendary not only for their superb work and high productivity, but also for standing up for the dignity of artists as workers and important contributors to society, and for the place of sculpture among the fine arts, especially (which was not always so certain a ‘belonging’ as it nowadays seems).

Their studio and house held warm welcome for artists throughout the city who loved to visit “The Church” – since it was one of the greatest natural creative and intellectual salons Toronto ever had. Their friends A. Y. Jackson and Lawren Harris (who lived just down the hill in Rosedale) from the “Group of Seven” were only two of the most notable of many prominent figures one might run into there. But I am certain that their generous and encouraging effect on the lives of young artists starting out was even more profound and impactful – and for several generations of creators.

Throughout their creative lives together, Loring preferred working on a very large scale – Wyle, on smaller pieces. Wyle even quipped once that “Loring doesn’t like a project unless it involves a ladder”. Wyle’s medical studies made her a master of precise anatomical detail. She was also a poet, and of the two, did work which was more overtly expressive, sometimes referencing the classical in form, and sometimes outright erotic (for the times).

While looking into one of Loring’s best known portraits – a bust of the co-discoverer of Insulin, Dr Frederick Banting, which is now in the National Gallery of Canada, I discovered that Banting and A. Y. Jackson were friends – and travelled to the far north together, after which Banting famously brought great shame on the Hudson’s Bay company, for their treatment of and effects on the indigenous communities in the north – even though the comments which caused such an uproar in the press were supposed to be off the record.

The Governor and general manager of Hudson’s Bay Corporation caught up with Banting at the King Edward Hotel a month later and demanded a public apology. He apologized for the reporter leaking his off-the-record comments, but refused to retract any of what he had said, because it was the truth. Thing is, neither the governor or general manager had ever been to the north, where Banting not only had – but with a doctor’s eye – so the confrontation ended with the two corporate titans asking him for advice on how to improve the whole situation. Hard to imagine a resolution like that nowadays, right? We are so much more interested in being angry, than in learning from contrary sources and thus improving those things which rightly anger.

I imagine Jackson, who told this story in his autobiography, must have brought his good friend Banting – who was himself a devoted amateur artist for the last twenty years of his life – by ‘the Church’ for at least one visit (and who wouldn’t come back for more of such a fine salon?). So Loring was probably sculpting a pal, almost as much as she was a paying tribute to a medical hero and great public figure when she made that, one of her own favourite pieces.

In 1928, Wyle and Loring helped found the Sculptor’s Society of Canada, which was also headquartered at “The Church” for many years and happily persists to this very day (now on Church St – a local artistic expedition which I must and will make soon).

Loring was especially relentless in the promotion of the arts, and was the key force behind the founding of the Canada Council of the Arts, which has done a great deal to help creators secure funding to bring their visions to the public. As Brian Eno once said admiringly, in an autobiographical sketch (I paraphrase) “They grant artists less than those on welfare get – but the artists are filled with pride and delighted to have it, and often do extraordinary work with these limited means.” He’s not totally right – but he catches the gist. Super helpful arts program to this day.

I am going to make it a small personal mission to locate and photograph many more of Loring and Wyle’s public works, as things gradually ease back toward full-open (and my legs ease back into distance-functional) – but I thought for today, it was worth looking at these two portraits a few times each. These sculptures regard each other in the park named after “The Girls” right next to the site of “The Church” and they were made just after they came to Toronto together, so we see Wyle at 33 and Loring at 27. Though still early in their sixty year relationship, they already show wonderful perception and depth, without any cheap sentimentality. Honest strength and beauty.

Sculpture always frustrates me as a photographer – even more intensely now that I have had the experience of sitting as an art model for hundreds of students, learning to create realistic sculptural portraits (busts). You can show a lot about a sculpture in a photograph, but you are always leaving a lot out, also. Even shifting the angle in a portrait just a bit, can give us a whole different and very distinct insight into the subject.

These two – already so solid a unit – and with more than a half a century of partnership ahead of them, saw so much in each other, that I was still seeing new and interesting angles worth photographing in their elegant busts, when my old-man back started acting up! Squat-balking, to be specific (and three cheers for Jimmy McGill).

But I love the fact that these two are still together in their good place. This sort of sculpture really does have magical inertia – even for hard core rationalists and materialists.

Wyle died on January 14th, 1968 – Loring passed just three weeks later, on Feb 5th.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

PS – Can someone please write a spirited one-act play with Emma Goldman (who also lived in Toronto several times, during their long residence) visiting them at “The Church”? Not only would that be some of the smartest feminist dialogue in ages – I am pretty sure that some of my friends would get commissions, to decorate the studio/home set, in dazzling fashion.

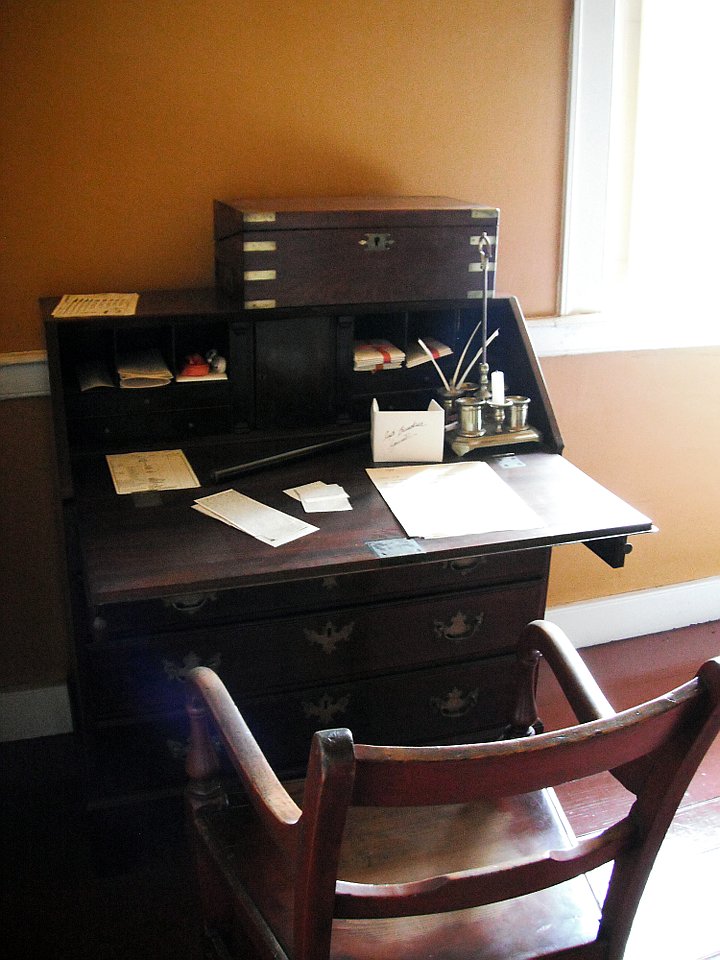

(Studios of every kind have that same magical creative inertia – they want you to get the work done!) Put that on stage, a lot – like, constantly – PLEASE! ;o)

——-

This was a truly joyous research discovery. Here is an especially lovely treat from the archives of the CBC –a peek inside “The Church” of Loring and Wyle in active studio mode – with some lively insights about art and life from both.

And finally, one of the two historical markers which add context to the park.

Two really nice bonus clues about the character of already impressive Frederick Banting, that I discovered while doing this research.

One – he is still the youngest Nobel prize winner in the field of medicine (32), but the award was officially shared with JJ McLeod, who helped him secure research facilities, and also suggested his promising research student Charles Best. Modern eyes credit the discovery to Banting and Best, rather than Banting and McLeod – but even at the time, Banting shared half of his prize money with the far junior Best, and McLeod also shared half of his prize money with James Collip, who also made very important contributions. Extraordinary respect and fairness for junior partners which we would not expect to see nowadays.

Even better, Banting did ultimately achieve some fair artistic talent – enough that more than one person asked about buying one of his paintings. But his response was always – “Go buy a Lismer (from the Group of Seven) or some other active professional artist, and I’ll trade my painting for that.”

¯\_(ツ)_/¯